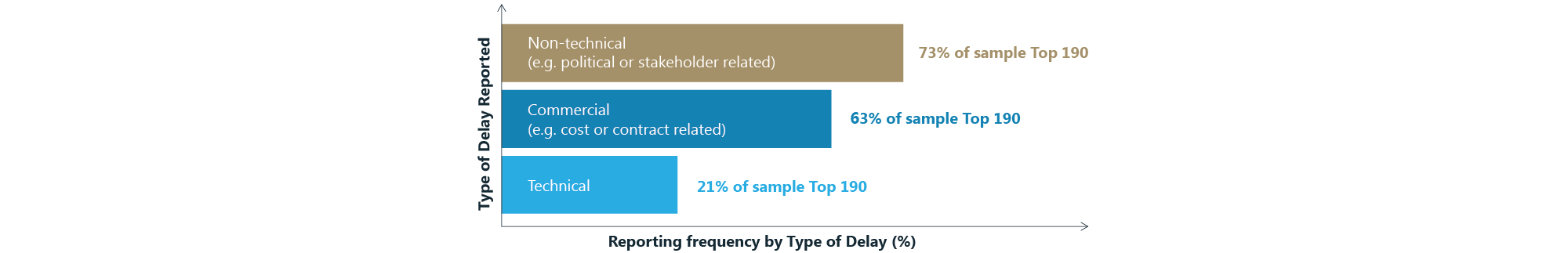

Non-technical risks are often ill-defined, and project delivery teams composed of technical people with a wealth of experience in their fields are often ill-equipped to know what to do about them. These risks can all too easily go in the ‘too hard to think about’ bucket – and once there, they aren’t managed or mitigated.

Non-technical risks may not be equal for all the technical options under consideration for a development. By asking the hard questions – ensuring that our framing and risk management processes ask questions about non-technical risk – right from the outset, means options are evaluated on an integrated basis, and the best overall option is recommended. Where complex risks cannot be eliminated by nature of the option selected, they're identified early and effective management plans can be set, running in parallel with technical scope.

It’s all about the framing

Framing, Framing, Framing. And again: Framing. Framing with a capital F. It is absolutely vital that the whole team understands the needs and constraints underlying the project, as these inform the way we do the work and the decisions we take. There is no such thing as ‘too busy for Framing’ – in fact, the shorter the schedule, the less the team can afford for someone to spend time lost down a blind alley. Framing workshops can vary from a couple of people round a whiteboard for an hour (for a fairly simple task), to a room full of people for a couple of days (for a complex project). Be proportional.

Framing workshops help to align the team and make sure everyone understands the objectives, constraints and decision criteria. Once you’ve got this alignment, the team will have what they need to be making project-appropriate decisions every step of the way.

At Advisian, we start every piece of consultancy with a facilitated Framing workshop with the client because we believe having better understanding of our client’s needs enables us to deliver the most appropriate solutions.

It’s all about the bass

Infrastructure, civil and structural works are often a far greater portion of the project total installed cost than the process equipment –another reality check for process engineers!

Concept selection studies are typically performed by teams with a high proportion of process engineers. Generally this is a good thing, because we're trained to think about systems holistically. However, sometimes we need reminding that the effort and level of attention given to various subjects should be in proportion to the impact they make on the overall decision – not in proportion to how close they are to our own technical specialism. Just because it doesn’t appear on a process flow diagram, doesn’t mean it isn’t important. See section 1 – it’s still not all about the process.

It’s all about the ker-ching, ker-ching… or is it?

Engineering contractors (and indeed client project teams) can easily fall into the trap of thinking that minimum CAPEX is the right answer to every question. CAPEX is important, but rarely the whole story.

Does it make sense to spend a bit more on CAPEX to reduce OPEX? On a piece of equipment we believe will be more reliable than a cheaper alternative? On something that reduces our energy usage? How about a location which makes construction more expensive, but is likely to have less community resistance (and delay) than the alternatives? How about pre-investment in design for decommissioning: reducing the decommissioning liability cost that the asset owner will need to carry on their books?

Rather than just CAPEX, wise decisions take into account the trade-off between costs and benefits over the asset lifecycle. Net present value (NPV), time to break even, return on investment and hurdle rates matter much more in the big picture.

By integrating various structured decision techniques into our technical consulting work, Advisian enables our clients to make sound decisions based on transparent, appropriate and robust criteria.

It’s all about the schedule

The premise behind front-end loading is that time spent on robust concept identification, screening and selection, is time well-invested. A wisely selected concept will result in good asset outcomes, even if there are bumps on the way in project delivery. Conversely, if the selected concept is a poor choice then it will result in a poorly performing asset – that early flaw in judgement can’t be rescued by the project delivery team even if they bust their guts trying - and even if their execution is flawless.

The most valuable article – bar none – which I’ve ever read on project management is one called 'The $2000 manhour' by Ken Cooper 2. It was published in 1994, so those manhours would be much more expensive today. The article explains far better than I could about the perils of an unrealistic schedule, and why it's counterproductive to beat a project team for failing to deliver something which was always impossible. How many projects across industry have an ‘official’ schedule which is shared with the client and a ‘shadow’ schedule which the discipline leads are working to? A realistic and coherently-planned schedule will result in a faster ACTUAL start-up date of the asset than an overly-aggressive fictional schedule with all its associated rework, increased costs and frustration.

If I could, I would make that article mandatory reading for every project engineer and project manager across industry. In fact, I would make them read it out loud and whack them on the head with it at the end of each paragraph. Thus speaketh a lead engineer who has performed damage-limitation of chaos caused by project managers promising the impossible.

Sometimes, it’s all about the farming

A few years ago, I had the privilege of working on a concept selection study which turned my thinking about concept studies on its head. See section 1 again – it’s STILL not all about the process.

Our objective was ostensibly to identify, screen and recommend the best concept to make use of natural gas in a developing country with large gas reserves. We compared technologies, we looked at potential locations, we estimated CAPEX, OPEX and NPV, we thought about community engagement programmes for the villages which would be relocated, we made projections for local employment in the workforce (both skilled and unskilled) throughout the life of the asset.

Do you know the one thing that made a significant difference between all of our options? Farming.

The country was dependent on import of refined products for all liquid fuels. Demand for diesel and gasoline exceeded supply, and when fuels were available they were subsidised by the government as international market prices were way above affordable levels for most of the population. A large percentage of the population rely on subsistence farming to survive. Any of our options that improved the availability and affordability of diesel for agriculture unlocked significant benefits across the whole economy.

As someone who grew up in a farming area, and drove farm machinery years before I could legally drive a car on the road, this resonated strongly with me. There is very little – not even healthcare or education, and I feel very strongly about those – that is as essential as growing food or providing access to clean water. Technology for its own sake doesn’t actually mean much, but technology wisely applied can make the world better than we found it.

Without thorough framing with a wide group of stakeholders, and without the humility to question our assumptions when the data told us something unexpected, we would have missed the point completely.

Sometimes, just sometimes, it’s all about the farming.

References

-

From Shell presentation “Managing Non-Technical Risk at the Project Level” at Social and Environmental Risk Management Conference, 2011; adapted from Goldman Sachs Investment Research “The Top 190 Projects to Change the World”, 2008.

-

http://www.pmi.org/learning/library/influence-project-performance-rework-cycle-2123/